It’s no secret that I love the writing of Shirley Jackson, but I must confess that when I first read the first few chapters of The Sundial, I got lost in the sprawling character landscape. I’m not the fastest reader in the world and I’m neither the most adept at mentally mapping who is who nor the most acute at discerning the symbols and subtexts of a work like this with a single, linear reading. I found it necessary to stop, go back to the beginning, take my notebook and pencil, and trace who is who to lay foundations for my enjoyment of the book. I’m glad I did, however.

This, I hope, can be something of the reader’s companion that might have helped me. At the very least, I hope it stimulates the reader to think more about the book. I hope it might enrich your experience of it.

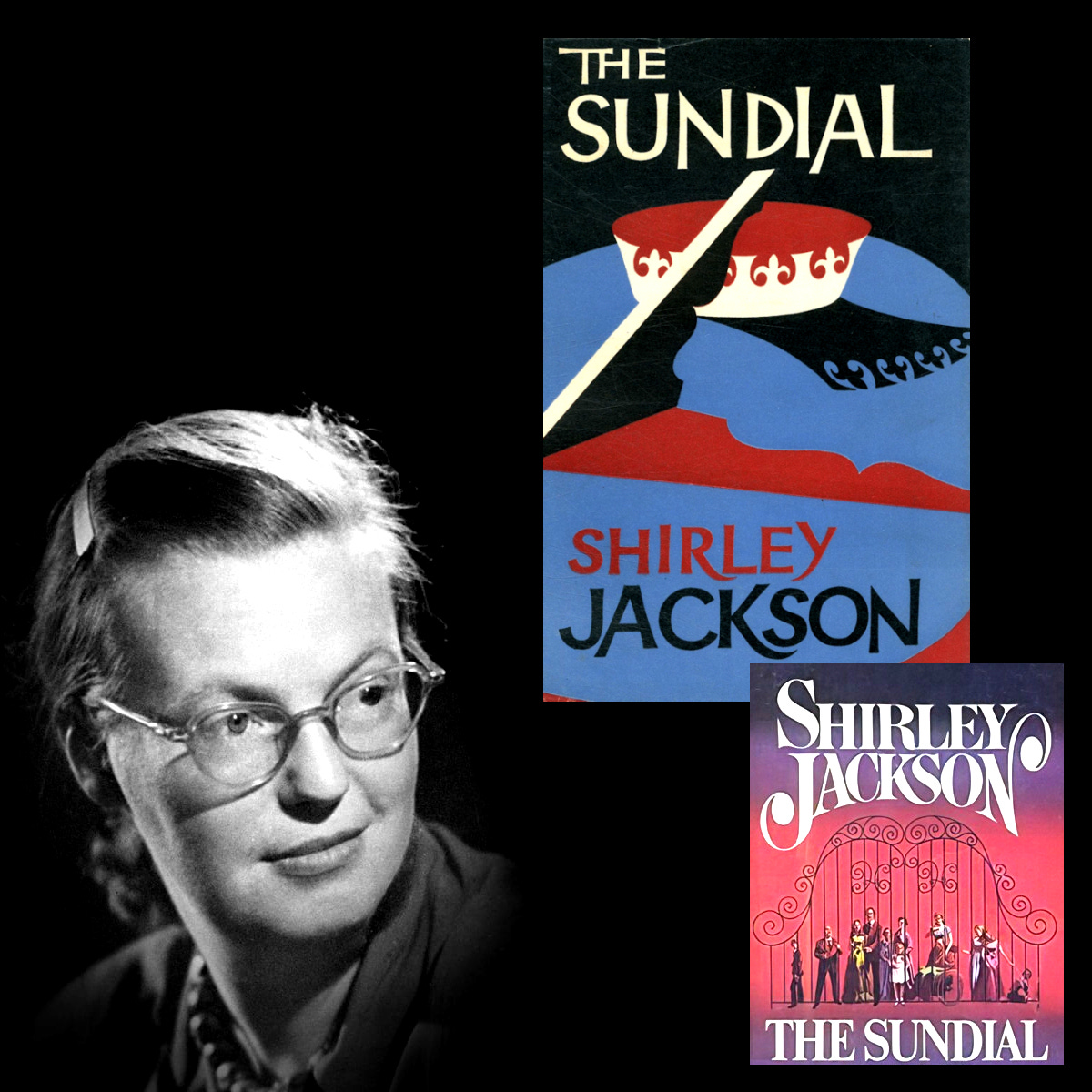

Introducing the Novel

The Sundial tells the story of a power struggle in the household of the wealthy Halloran family. It is set in motion by the death of Lionel Halloran, the owner of the house; and catalysed by a vision that comes to Frances Halloran (“Aunt Fanny”), Lionel’s spinster aunt. Her dead father appears to her at the house’s titular sundial to deliver a doomsday prophecy and promises that those who seek the protection of the house will be saved.

The Sundial is ultimately an apocalypse story. Well, to be more accurate, it’s a pre-apocalypse story, or perhaps even more accurately, an apocalypse anticipation story. As the power struggles play out in light of the doomsday prophecy, and characters vie for relevance and, in some cases, dominance, the novel shines a light on many social absurdities:

Class and inheritance of power.

Power grabbing when survival is on the line.

Human vanity and selfishness.

Insularity.

Religion, true belief, and zealotry.

The novel also mocks human archetypes by exaggeration:

The cruel matriarch.

The passive patriarch who looks the other way.

The spinster who apparently does not have romantic needs.

The friend with an ulterior motive.

The house is set near a village and like every village Shirley Jackson created, it is rife with suspicion, cliques, secrets, and gossip.

Genre and Readings

One of the many things I love about Shirley Jackson’s writing is that it crosses genre boundaries and can be read in different ways. One can choose the lens one reads it with and read it again through different lenses.

On one hand, The Sundial a gothic folk horror tale that occurs in the backdrop of death and portrays the cruelty people in insular communities inflict on one another in the desire for power and zealous belief.

At the same time, it’s a social satire and a black comedy.

By calling the novel The Sundial, we’re begged to seek a central significance in the object; and as such we might read it as a philsophical tome that contemplates the inscription: “What is this life?”

It can also be interpreted as a disturbingly prophetic metaphor for every insular community that has become an echo chamber as it shuts outsiders and inconvient ideas out, by mockery and fortified walls.

That latter reading, by the way, makes this 1958 work a prescient mirror on the problems with political discourse and the formation of hard-line cults that we see in today’s society.

The House as Prison and Sanctuary

A common theme in Shirley Jackson’s novels is the house as a causal agent in the story. It is silent, but seemingly omniscient and potentially the magnet, or perhaps even the source, if we’re so poetically minded, for the malevolence we meet within its walls. In its silence and stillness, it is at least a shell for the psychological oppression that occurs within it.

The house is also both a prison and a sanctuary. This is a seemingly universal theme in Shirley Jackson’s novels where there is an imposing, central house figure. Those who wish to escape the prison, such as Julia Willow, risk doom. Those who seek the safety of the sanctuary, such as Miss Ogilvie, must surrender their identity and dreams.

One might be critical of the extent of the recurrence of this theme in Shirley Jackson’s novels, but I, for one, love it when there are recurrent themes in a writer’s work; and I love this theme in particular. It enriches the critical observation of the writer’s body of work and its meaning. Obviously, it links The Sundial with Jackson’s famous novels, The Haunting of Hill House, and We Have Always Lived in the Castle.

Characters and Ambiguity

The Sundial is a novel with a large cast of characters.

In summary:

Michael Halloran, the original Mr. Halloran — deceased

The original patriarch of the Halloran house who died long before the novel opens, Michael chose the site for the house and had it designed and built. The sundial and the maze were key features he desired.

Although he patronized and supported the village, as does the continuing Halloran household, he also looked down on the villagers and preferred to hire staff from the city.

Anna Halloran — deceased

The wife of the Michael and mother to Richard and Fanny. Anna apparently died quite young, long before the novel starts. A statue of her stands at the centre of the maze. Make of that what you will.

Richard Halloran

The son of the original Mr. Halloran and husband of Orianna. Richard is old and wheelchair bound. He appears to be in mental decline and is tended by a nurse. The novel occasionally includes poetic, prescient passages for the reader which are read by the nurse to him.

Orianna Holloran

The self-styled matriarch of the Halloran house after son Lionel’s death, Orianna claims possession of the Halloran house. She is a cruel and domineering character who wants to consolidate her control over others.

Lionel Halloran — deceased

Orianna and Richard’s son, Lionel was the owner of the Halloran house prior to his death just before the start of the novel. His death is what creates the power void that other characters move to fill.

Frances Halloran (“Aunt Fanny”)

Richard’s sister and daughter of Michael and Anna, Frances is a spinster who has always lived in the Halloran house. She is outwardly weak and meek, seemingly not wishing to be a burden on anyone.

Prone to visions — or hallucinations — the doomsday prophecy she brings to the Halloran household punctures Orianna’s dominance and becomes the catalyst for the household breaking into camps.

Although it is conceivable, at least in the early part of the novel, that Fanny is playing a power game with the prophecy, the novel indicates she experiences the visions as real and is convinced prophecy is true. It is still possible, however, that it could be an unconscious power play.

As an interesting additional dimension to her character, we meet her, more than once, knocking on men’s doors at night saying, “I’m only 48.”

Make of that what you will!

Maryjane Halloran

Lionel’s widow and mother of Fancy, Maryjane is nevertheless the outsider within the family and is left at the mercy of Orianna when Orianna claims the house. She believes Orianna killed Lionel for the house.

Fancy Halloran

Lionel and Maryjane’s precocious daughter, she is apparently prone to lying and spying. Seemingly amused by Orianna’s cruelty, she is chosen by Orianna to be heiress to the house and the matriarchy.

Miss Ogilvie

Fancy’s governess. She is a member of the household but as she is not a family member, she identifies as an outsider, along with Essex.

Essex

Hired to catalogue the Halloran library, Essex is philosophical and appears to have romantic aspirations, tending to flirt with the females.

Augusta Willow

An old friend who invites herself as visitor, she has a somewhat barbed relationship with Orianna. As mother of the two “gels” Arianna and Julia, she seems short of money and desperate to either marry her daughters off or gain money by other means.

Although she initially claims to be a spiritualism skeptic, she introduces the house to the practice of using an oiled, old mirror to see the future, principally through the character of Gloria. Through this, she becomes a competitor of sorts to Fanny and a further foil to Orianna.

Julia and Arabella Willow

Augusta’s daughters. Julia is signalled to be the rebellious one who has romantic aspirations and yearns to be free.

Gloria Desmond

Aged 17, Gloria mysteriously appears during a bridge game and becomes a medium for Augusta with her oiled mirror routine. This might make the reader suspicious that her arrival is a contrivance by Augusta to insert herself into this wealthy household and gain influence.

Gloria claims her father is a cousin of Richard’s who is away in Africa shooting lions and sent her to the Halloran house to stay.

“Captain Scarambombardon” (Harry)

Seen by Fanny during a trip to the village, he is invited into the household to bring what Fanny perceives to be a much-needed male into the house as it prepares for the apocalypse. She’s only 48, remember.

To maintain the pretence that he was chosen for probable military skill, Fanny calls him Captain. We later discover he’s a drifter called Harry who is content to insert himself into the wealthy household.

This character represents false identities, temptation, escape, and an alternative to Halloran control; and is sometimes used by Jackson as a device to break the claustrophobic sameness of the household.

The Halloran House Itself

The house is grand in conception but ageing. We learn it was built just after a sensation that brought notoriety to the nearby village — that of Harriet Stuart, who apparently murdered her family with a hammer.

The house has a large library that is being catalogued by Essex, large grounds with a maze that leads to the statue of Anna, and a sundial which seems to be at the heart of the supernatural visions.

Symbols and Devices

As always, Shirley Jackson’s writing provides us with a wealth of inexplicit symbols to make sense of, and begs many questions the reader must contemplate for themselves.

The maze.

The sundial and it’s inscription.

The legend of Harriet Stuart, potential murderess.

The doll’s house made in the image of the Halloran house.

The True Believers.

Some of these are easier than others. The maze is an easy symbol to decode. The Harriet Stuart legend justifies that there is a healthy economy of tourism in the village, but it begs more consideration, as simpler devices could have achieved the same. Does it suggest there is a malevolence that inhabited the village and then the house? Or is the Harriet Stuart legend what Alfred Hitchcock would call a mischevious maguffin? The reader must answer, because, of course, Shirley Jackson does not do so!

The True Believers is a village sect which believes aliens from Saturn are coming to save those who believe, but only those, from the coming end of the world. It’s a crazy belief, of course, but is it more crazy than the doomsday prophecy? The True Believers gives Jackson a device to ridicule the absurity of zeal and arguing between sects about whose crazy belief is real.

The doll’s house is a particulary interesting symbol, which comes to fruition as we confront the meaning of the book’s final chapter. More later.

The novel contrasts childlike simplicity with adult complexity and explores the themes of insiders, outsiders, and parasites through the lens of the small, insular, house-bound commune.

To that point…

Interpretations of the Final Chapter

(Spoiler Alert!)

The book is at its most fascinating when we contemplate the meaning of the final chapter. Sadly, it is impossible to do this without spoilers. Avert your eyes if you have not read the book yet!

Is it Poetic Justice?

Did Orianna die in the same way that some people believe she killed Lionel, so she could assume possession of the house? Augusta Willow seems to think so. Was it Fancy who killed her, to achieve the same?

Is Fancy the a Puppet Master?

As the owner of the doll’s house, which is in the image of the Halloran house, can we conclude that Fancy is the puppet master all along, even if unconsciously? Could it be that she is the medium for the malevolence?

Is History Repeating Itself?

When Fancy takes Orianna’s crown and Gloria takes the doll’s house, is this Fancy and Gloria become the new Orianna and Fanny? Has this happened before? Will it happen again?

The Absurdity of Inherited Rule

We already confronted this, but it is worth calling out again. Fancy emerges as the new ruler of the Halloran house, but she is a child.

Did the Mirror Tell the Truth?

Gloria said that Orianna was not in her visions for the future and, indeed, as we discover, she was not going to be. Does this indicate that the mirror routine yielded true vision?

Was the Prophecy Real but Misinterpreted?

Everyone assumed the doomsday prophecy was about a physical destruction of the world outside the house. Perhaps Fanny’s father did save the household from destruction, but from a destruction of a different kind — psychological destruction happening inside the house, by Orianna.

Is Everyone Ultimately Imprisoned by Their Belief?

Ultimately, it looks like it is the characters’ beliefs in the prophecy, who they are, and where freedom and safety exist, which imprisons them.

Will Anyone Escape?

We never get to find out if an outer world apocalypse happens. We never get to find out what happens when the servants return, if it doesn’t. However, along with the idea of history repeating itself, with the cycle repeating in an increasingly insular house, will anyone ever truly escape?

On The Other Hand…

Is our author simply playing a game with us? None of this, after all, is made explicit. Is it all just coincidence that has no real meaning? Is our need to make meaning that is being mischeviously played?

This is the delight of reading Shirley Jackson!